THE BATTLE OF OTTERBURN - 1388 |

|

The Battle of Otterburn took place on 19 August 1388, as part of the continuing border war between England and Scotland. Partly fought in moonlight, it was a victory for the Scots, led by James Douglas, 2nd Earl of Douglas over Harry Hotspur, son of the Earl of Northumberland. Douglas was killed in the battle, though his victory added to the prestige of his house, foremost among the border fighters of Scotland. When the latest truce with England ended in the high summer of 1388 the Scots began attacks on both the western and eastern marches, taking advantage of growing divisions between the Percies and the Nevilles, the English wardens. In August the Earl of Douglas led a particularly bold move against the port of Newcastle. This was risky: he was not equipped to carry out a siege; Newcastle was one of the main muster points for English troops in the north, so it was likely there would be more soldiers inside the town defending than outside attacking; and with the Earl of Northumberland at Alnwick, there was always a danger that his retreat would be cut off. But the very audacity of Douglas' move had the effect of convincing the English that his force was only the vanguard of a much larger army close by. Frequent skirmishes took place at the outer defences of the western wall. In the account of Jean Froissart Douglas is said to have captured Hotspur's own pennon, though this story reads as if it has been added to provide some romantic colour, a technique in which the chronicler excels. |

he determined to set off in pursuit with all haste, before the enemy had a chance to slip back across the border. Hotspur had at his disposal some 8000 troops and, true to his impetuous nature, he decided to set off at once, rather than wait for reinforcements promised by John de Fordham, the Bishop of Durham. After leaving Newcastle Douglas moved in a north-westerly direction, making for the valley of the River Rede, intending to take the same route back to Scotland by which he had entered England. He was in no particular hurry, despite the obvious dangers of his situation. His force, of course, was weighed down with livestock and other booty; but when he reached the tower of Ponteland, a few miles from Newcastle, he paused to attack this unimportant obstacle, thus alerting Hotspur to the direction of his retreat. |

| Hotspur made good progress in his march from Newcastle, but it is likely that he believed the enemy to be further ahead. When he entered the valley of the Rede in the dying summer light of the 19th he was simply looking for a place to camp: his men were tired and stretched out in a long column reaching back to Ponteland. But there, a short distance to the front, were the Scots. Two choices were open to him: to wait for the morning, allowing his men to rest and regroup before beginning the battle, thus allowing the usual English superiority in the longbow to have its full effect; or to take the high-risk strategy of beginning an immediate attack, hoping to gain the advantage of surprise. Hotspur would not wait for dawn: battle would be joined at once. To prevent the Scots slipping away he detached part of his force on a wide sweep to the north, past the Scottish left flank and then, in the word's of John Hardyng's Chronicle, to "holde them in that they fled not away" while the main body of the army launched a frontal attack. With the sudden approach of the English in the fading light there was considerable confusion in the Scottish camp, taken by complete surprise. The Chronicle of Pluscarden describes the scene thus; |

|

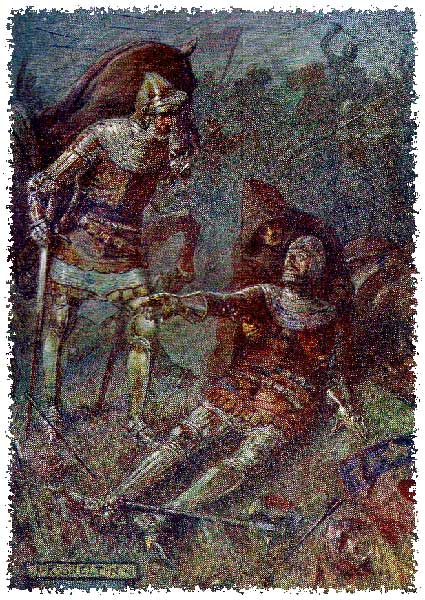

| They rose at once and rushed to arms, but scarcely could a bare half of them arm themselves. The Earl of Douglas also rose, and in his haste could hardly put on his armour or fasten it with the buckles, owing to the confusion of the sudden onslaught of the enemy; so he rushed forward with uncovered face to marshall the line of the battle. Gathering as many men as he could Douglas began a counter-attack that was to win him a battle and immortality. He approached Percy's right flank to the north, racing swiftly along a wooded hillside, with a slight depression covering his approach for the last two hundred yards, before falling on the astonished Englishmen by the light of the autumn moon with loud cries of 'A Douglas!' 'A Douglas!' The ensuing battle was one of the strangest in all the Anglo-Scottish wars. Because of the poor visibility Percy was unable to make effective |

| use of his archers. Each man fought in a grim hand-to-hand contest, with only enough light to see for a short distance around him. The spectral combat ceased whenever clouds flitted across the face of the moon, allowing all a welcome rest in the darkness, only to begin again with renewed vigour when the wind carried them past. In these conditions the combat continued for several hours, amidst the shrieks of the wounded and dying, over ground slippery with blood. At some point during the night Earl James was killed, but by whom and in what manner is unknown, despite Froissart's theatrical account. Andrew of Wyntoun, the Scottish chronicler, simply says; "Bot |

Errl James thar was slane, that na man whist on quhat manner." His body was found the following morning, stripped of his armour and with a great wound in his neck. Unaware of his death his comrades fought on, steadily pushing the English downhill. As dawn broke Hotspur's army began to crumble, with men fleeing the field in increasing numbers. Hotspur was taken prisoner, as was his brother, Ralph, who had been badly wounded. Altogether over 1800 men were slain or captured. A number of Scots were also taken prisoner in their over-hasty pursuit of the English.

|

|

When the Battle of Otterburn was being fought the Bishop of Durham was on his way from Newcastle with 2000 cavalry and 5000 infantry. They arrived at Ponteland on the morning of 20 August, where they met groups of men fleeing from the battlefield, which had such a demoralising effect that the whole force retired. The principal cause of the English defeat is simply stated-Hotspur was a brave soldier but a bad commander, a truth summarised by the Westminster Chronicle; The calamity that befell our countrymen on this occasion of Otterburn was due in the first place to the heady spirit and excessive boldness of Sir Henry Percy, which caused our troops to go into battle in the disorder induced by haste: and in the second place because the darkness played such tricks on the English that when they aimed a careless blow at a Scotsman, owing to the chorous of voices speaking the same language, it was an Englishman that they cut down. When news of the defeat reached London the search for scapegoats began immediately. The obvious candidate was the Bishop of Durham, who was criticised by the Royal Council for arriving too late to help Hotspur. Curiously, no official blame was attached to the commander himself for his military incompetence. He was generally perceived as a rather heroic figure, with King Richard and Parliament both contributing towards the cost of his ransom. |

The body of Douglas was taken back to Scotland and buried with all honour beside that of his father at Melrose Abbey. |

|

© Paisley Tartan Army 2008-09